For my generation — specifically, those of us born in the late 1980s — the world has grown smaller as we’ve grown bigger. Our maturity has been matched almost step-by-step by the maturity of digital technology. One could argue that no generation has ever seen the world change so much, from a communications standpoint, as The Facebook Generation.

When we were born, computers were the New Kids on the Block. My family had an old-school, black-and-white Mac that ran the MS-DOS operating system and would seem as primitive as cave drawings to today’s iMiracles. During our adolescence, cell phones were larger than infants and came in briefcases. My family had in-house portable phones — how cool it was not to need a cord! — and my dad wore a beeper. We had VCRs for our movies, Walkman players for our music, and the original Gameboy, SEGA and Nintendo systems for our video games.

It all changed, at least as I recall it, with Microsoft Windows and a little thing called America Online. We would come home from middle school and rush to listen to the clicks and screeches of our dial-up modems (listen), facing the world for the first time as digital representations of ourselves; my first “screen name” was Jr24BigMac (inspired by Ken Griffey, Jr. and Mark McGuire).

Around the same time — seventh and eighth grade — our parents started reluctantly giving my friends and I our first cell phones. They were the old-school Nokias, the highlight of which was the Snake video game. (Recently, I heard of a parent who bought her seven-year-old a BlackBerry. When I was seven, those still grew on vines.)

When Apple came out with the iPod, we realized we were headed far away from Kansas. My dad’s entire record collection, which previously occupied a wall of our house, could now be easily compressed into something that fit in a pocket. Since then, the technology has only gotten crazier, and people have more or less become fused to their machines. It will not surprise me one bit when they start fitting babies with USB ports.

Nothing, though, hit my generation like Facebook. It re-wrote everything. (You could argue this point — in terms of worldwide impact — in favor of the Internet, or Google, or Twitter. For the college graduating classes of about 2008-2010, though, Facebook takes the e-cake.)

I first heard about Facebook from a girl named Jenna during my senior year of high school. She had graduated the year before and was a freshman at the University of Maryland. I was talking to her under my second AOL Instant Messenger alias — DedSxy30. (Inspired by Austin Powers, I employed it primarily because I thought girls would like it.) She told me about this new thing called Facebook that only people in college could have because you needed a college email address to join the network. Rest assured, I registered on Facebook almost the minute I received my official @email.unc.edu address.

Those were the Wild West days of Facebook, when it was normal to friend people you’d never met. I had a whole group of ‘friends’ before I arrived at school, and it was nothing strange to see each other at a fraternity party and be like, “Hey — I know you from Facebook!” Back then, you had one profile photo. One. And a wall, groups and interests. That was pretty much it. The news feed consisted of up-coming birthdays. If you wanted to share pictures, you used Webshots or something similar. MySpace was still a thing.

Then they let high school kids join the party. Then people in professional networks. Then moms, dads, grandparents, babies and dogs. They added unlimited photo upload capacity, Facebook Chat, apps, ads, and all the bells and whistles that you see today.

The world will never be the same.

Imagine: In 10-15 years, the way people communicated, shared their experiences, and interacted with the world and each other changed so much that to the outside observer it would seem nothing short of science fiction.

For people my age, those 10-15 years were the ones that marked our journey into adulthood. We are irrevocably linked to these developments, which matched our development. One day, we were in grade school, learning to hand-write and address letters to pen pals, practicing typing on desktop computers the size of buses. The next day, we were preparing for life in the so-called “Real World,” writing 25 emails and 50 text messages a day from our phones, which never left our sight.

Is this for the better?

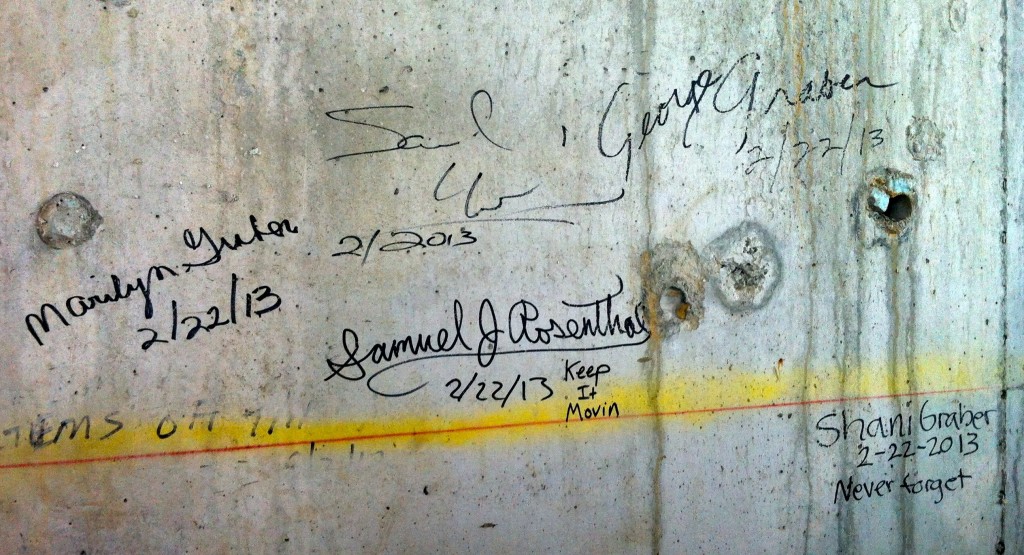

It seems that the more in-grained we become in our social media, the less social we actually are. Take it from the guy whose friends once created the virtual group “Sam Rosenthal’s Obsession with Facebook is Disturbing.” It is now totally common to sit in a room with five young people — all of them on their Smartphones, computers and tablets, none of them saying a word to each other.

These networks may sap our net worth; there’s something about broadcasting yourself to the world as a series of images and words that, as we become more connected to our machines, increasingly disconnects us from each other — and ourselves. It is almost as if there are multiple versions of us — who we are in life, and who we are online. What scares me is that every day that passes, the latter seems more and more like the reality that matters to us.

There are two terrific articles that delve into the specifics of just how new-age technology is changing us. Neither is short — gasp! — but both are well worth reading.

One, a recent piece by Matt Labash in The Weekly Standard, describes “The Twidiocracy: The decline of Western civilization, 140 characters at a time.”

“I hate the way Twitter turns people into brand managers, their brands being themselves,” Labash writes. He adds: “A technology that incentivizes its status-conscious, attention-starved users to yearn for ever more followers and retweets, Twitter causes Twidiots to ask one fundamental question at all times: ‘How am I doing?’ … Even the most independent spirit becomes a needy member of the bleating herd.”

Most of what he writes about Twitter applies to Facebook and the rest of social media, which are quickly becoming the filter through which we view real-life experiences — and, as I see it, a separation from those experiences. Every time you take a photo of something, or make a status update or a Tweet, you remove yourself from the present moment. The impulse is to capture the moment, rather than participate in it.

Labash describes attending a speech given by Luminate’s Chas Edwards, who cited the statistic that “10 percent of all the photos ever taken have been snapped in the last 12 months.”

“As Chas speaks,” Labash writes, “most of the room is looking down into their iAbysses, thumb-pistoning away. He observes that ‘only 10 percent of you are actually consuming me. What I’m hoping is that the other 90 percent of you are online enjoying more fully this experience and tweeting it.’”

In the article, Labash describes attending a panel entitled “Are Social Media Making Us Sick?” And although the social media gurus say, “No,” — giving the author “the feel of tobacco company ‘scientists’ telling us smoking increases lung capacity” — most of the new-age crowd answers, “Yes.”

“And never mind,” he writes, “a Michigan State study that found excessive media use/media multitasking can lead to symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. An Oxford University scientist said Facebook and Twitter are leading to narcissism and an “identity crisis” in users … A Chicago University study found that tweeting can be more addictive than cigarettes and alcohol … German university researchers found one out of three people who visited Facebook felt more dissatisfied with their lives afterwards, owing to feelings of envy and insecurity.”

Heck: “A recent survey by Boost Mobile found 16-25-year-olds so addicted that 31 percent of respondents admitted to servicing their social accounts while ‘on the toilet.’ And a Retrevo study found that 11 percent of those under age 25 allow themselves to be interrupted by ‘an electronic message during sex.'”

In his 2008 article “Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is doing to our brains,” The Atlantic’s Nicholas Carr takes a broad look at how the Internet Age is re-wiring the way we think. He describes how he and his colleagues can no longer read long texts like they used to, and he feels it is because the multi-tasking, multi-channel realities of today’s media landscape fragment our attention and prevent us from concentrating or contemplating the way we previously could.

Carr’s article focuses less on social media, but it poses incredibly important questions about the direction in which we’re headed. He looks at the mission of Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who “speak frequently of their desire to turn their search engine into an artificial intelligence, a HAL-like machine that might be connected directly to our brains. … In a 2004 interview with Newsweek, Brin said, ‘Certainly if you had all the world’s information directly attached to your brain, or an artificial brain that was smarter than your brain, you’d be better off.’”

This idea scares Carr: “It suggests a belief that intelligence is the output of a mechanical process, a series of discrete steps that can be isolated, measured, and optimized. In Google’s world, the world we enter when we go online, there’s little place for the fuzziness of contemplation. Ambiguity is not an opening for insight but a bug to be fixed. The human brain is just an outdated computer that needs a faster processor and a bigger hard drive.”

“Maybe,” he writes, “I’m just a worrywart. Just as there’s a tendency to glorify technological progress, there’s a countertendency to expect the worst of every new tool or machine.” He cites Socrates’ aversion to the written word, and Squarciafico’s to the printed one, as evidence of the fears of new technology. Although these fears often come to fruition, he notes that “the doomsayers were unable to imagine the myriad blessings” that the new technologies created.

Maybe I’m just a worrywart, too, but the motor of the digital world concerns me about the future of the real one. Social media may be making us sick, and they’re definitely not making us happy. Facebook and Twitter deal in compulsion, not happiness. We log on seeking approval, seeking a sense of self portrayed online. It is a virtual world, and as such it cannot provide more than virtual experiences. Once you’re logged in to a social site, your brain operates unconsciously. You browse, and click, and post, unaware of why you’re browsing or clicking or posting because it’s all on impulse.

I feel like Carr’s theory about our brains being re-wired is correct. If I walk down the street, not 20 seconds pass before some alarm goes off in my head: “Check email!” or “Any new Facebook notifications?” or “Who’s that text from?” The more we use our technology, the more we’re programmed to use it.

Last summer, I spent eight days at the home of some family friends in rural Sweden. No Facebook, no email, no internet. I meditated, wrote for hours, cooked, had real conversations with my friends, and engaged with nature. My mind was at ease.

On the train ride from Sweden to Denmark, I caved and purchased a half hour of internet access. For that half hour, my brain entered Online Mode — one with the machine, completely out of touch with everything going on around me. There I was, hurtling through the Swedish countryside on a glorious morning, and all I could do was get stuck in my Bermuda’s Triangle of Facebook, email and fantasy baseball.

When my internet cut out after the half hour, I slunk back from my computer, my head pounding. “What just happened to me?” I thought. After a week without that feeling — a week without connecting my brain to that unconscious current — I became acutely aware of the empty, compulsive addiction brought on by the Net.

It wasn’t always like this. I was young, but I remember a time before people became virtual representations of themselves. My generation — the Facebook Generation — may be the last of its kind. Today’s kids have no concept of a world without user names. From the moment you’re born, now, you’ve been Facebooked, Instagrammed, Tweeted and Vined. You’ve been ‘liked’ and ‘followed’ so much, you’d think you’d won something. What have we won? More importantly: What have we lost?

Like Nicholas Carr, I, too, see danger in the dreams of Google’s founders. Syncing the human brain to artificial intelligence may provide us with unlimited mental resources, but at what cost? If we are being wired by our machines to think more like them, we risk losing the ability to think and be like humans. If we are constantly projecting ourselves, via social media, at what point do we forget that our Facebook profiles are not who we are? At what point does the digitally-projected self — the “personal brand” — become more important than the complex, ambiguous phenomenon that is the human being? At what point do we become permanently severed from the present moment?

And can you please ‘like’ this article on Facebook?

by

by  by

by