Our feet wore heavy, solemn treads into the snow that blanketed the Berlin ground. We walked among the silent stones, which the German winter had shrouded in an inch-thick frost.

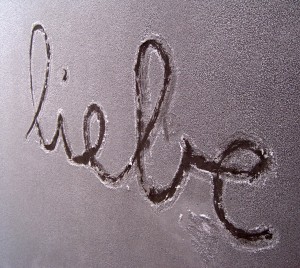

Using the frost like condensation on a bus window, visitors inscribed messages on the stone slabs. My friend Travis and I saw two European girls with SLR cameras slung over their necks. One, a 20-something-year-old redhead, traced a word onto the rock with her gloved finger.

“What does that say?” I asked her, hoping she spoke English.

“Liebe,” she said. “Love.”

It was my first trip to Germany.

As I am a Jew, it was no simple vacation; it was a chance to encounter a place which had possibly affected the course of Jewish history as much as Jerusalem itself, a place which had spawned the greatest atrocity mankind has ever known. A place that had fostered Hitler and the Holocaust and now, 70 years later, still bears the scars of every number the Nazis etched into human flesh.

Though it’s true that Berlin and Munich offered us plenty to enjoy, this trip was about more than bratwursts and brauhauses.

The Brandenburg Gate loomed behind me. Thousands of people milled about the structure, which dates back to 1791. The Prussian monarchs gave birth to it, Napoleon once stole a part of it, the Nazis made it a party symbol, and it formed the Berlin Wall crossing where people could (or couldn’t) enter and exit East and West Berlin.

In that moment, the Gate symbolized the country whose leaders and population had once made it their business to exterminate anyone with my bloodline … not to mention gypsies, Communists, Poles, homosexuals, the mentally ill or physically disabled, and anyone else who opposed them or failed to meet the criteria for their ideal, “Aryan,” race. Standing there — a Jew, a free Jew — filled me with a sense of defiant power.

“I am alive,” I whispered. “I am still here.”

Every story has at least two sides, and this one features the Germans as much as the Jews. Because of my Jewish and journalistic roots, it intrigued me to know what Germany’s like now, if people there talk about the Holocaust, if they feel shame or anger or remorse — to know if they care.

During our first and only night in Berlin, nobody uttered so much as the “H” in “Holocaust.” Waking up late the next morning, we had less than two hours to sightsee before catching a train to Prague. And that’s when it happened.

We approached the hostel’s front desk girl, Berlin city maps in hand. “What can we see in an hour and a half?” I asked her. “We definitely would like to do the Brandenburg Gate, and the remaining parts of the Berlin Wall are important, too.”

“To be honest,” she said, “the wall is not so interesting.” With a pen, she circled the Brandenburg Gate on the map, and another spot nearby. “From the Gate, you should walk down and see the Holocaust memorial. These two things you can do in time, and they are important.”

Boom — the first hint of the scar. It spoke volumes to me that a German girl, about 27 years old, recommended a Holocaust memorial to two random tourists. She had no idea she was talking to a Jew, yet, of all the sites in Berlin, she directed us to the Brandenburg Gate and “The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.”

It mattered to her.

There we sat in a dimly-lit, Bavarian restaurant in Munich, speaking English and Spanish with the joint’s German owner, when a couple sat down to our left. Christian looked to be 60-65 years old, and Anne Marie a few years younger, both German and decent English-speakers. We conversed a few times during the meal, and toward the end they asked us what activities we had planned.

“Actually,” I said, “we’re going to Dachau tomorrow.”

“You’re going to Dachau?” Anne Marie asked me. “Are you Jewish?”

“Yes,” I answered, knowing full well that there was a time when saying such a thing, in this very place, was a crime punishable by ignominious death.

“My daughter is Jewish,” she said. “She converted when she married my son-in-law, who is Jewish. We all have Chanukah together every year. Now, it is very multi-cultural here.”

Probably born at the end of World War II or soon after, Anne Marie told us her father had once concealed her Austrian heritage and told her she was Aryan — Hitler’s ideal race. When she visited Yad Vashem — the Holocaust memorial, museum and educational center in Jerusalem, Israel — she found out that her father had lied to her; she had Austrian, non-Aryan ancestors. She realized that “a person’s looks … blonde hair, blue eyes … these things cannot tell you who a person is.”

She had willingly visited Israel — Yad Vashem even! She had confronted her country’s past. “You can´t change the six million people,” she said.

But you can acknowledge their lives. And you can learn from them.

Dachau is a concentration camp. Was a concentration camp. The first concentration camp.

Dachau is a concentration camp. Was a concentration camp. The first concentration camp.

Our tour guide, Curt, reminded us that it stopped being a concentration camp on April 29, 1945, the day American forces liberated the victims. Predominantly male, political prisoners and later the whole host of Nazi enemies were sent there — more than 200,000 of them in 12 years. More than 43,000 died.

Now, a normal, suburban town exists next to Dachau’s borders. It was like that during the war, too, although the town’s borders were a tiny bit farther away then. According to Curt — an Irishman who’s lived in Germany for 10 years and has extensively studied World War II history — the townsfolk knew, or at least had some idea, what the Nazis were doing there. The town’s current residents naturally know what happened there as well, but they live seemingly oblivious to it; some of them walk their German shepherds outside Dachau’s walls. Curt made a sour face when he saw this. “Those are the dogs the Nazis used to murder people,” he said.

Before we entered Dachau, Curt addressed us: “This is not the kind of tour you enjoy,” he said, “but the other tour guides and I believe that it is by far the most important tour that we lead.”

Because it no longer functions as a concentration camp, Curt referred to Dachau as a “memorial.” Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary defines “memorial” as “something that keeps remembrance alive.” Dachau accomplishes this from the front gate — which bears the words “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Shall Set You Free”) — all the way to the secluded corner where the Nazis housed their machinery of death.

In between, you see the barracks, which were designed to house a couple hundred men … but often held a couple thousand. They slept on rows of wooden planks, head-to-foot, like sardines.

You see the main grounds where they held roll call, which involved everyone standing at attention, in all types of weather, for hours and hours. The guards humiliated people at roll call, beat people at roll call, and executed people at roll call. If any prisoners collapsed, and others tried to help them, the Nazis laid them all in the dirt.

You see “the bunker” — the torture chambers — where prisoners endured solitary confinement in utter darkness for days, weeks or even months at a time. The Nazis conducted “pole hangings” there: The process involved tying a man’s hands around a pole, behind his back, and dangling him above the ground until long after his shoulders broke into a position for which no human shoulder is made. Rumor has it that the camp archives contain a picture of two guards simultaneously jumping on a pole-hanging victim and disconnecting his upper body from his torso.

All this, you see. All this, you feel. All this, you try to understand. It is not easy.

It is not the kind of tour you enjoy.

We headed toward the crematoria.

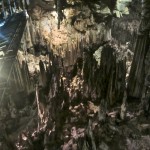

We walked the same path that so many had walked before — to their deaths — and traversed a five-foot-wide bridge that spanned a small stream. The stream ran smooth and black and indifferent, a liquid shadow, cutting through the snowy banks and disappearing into a thicket farther along.

“Even here,” I said to Travis, “there is beauty.”

The crematoria are not beautiful. They are ovens made for human beings.

But seeing them is all-important; humans must know what they are capable of doing to one another.

First, Curt took us to the “old” crematorium, so-named because prisoners started perishing at such a prolific rate that the Nazis needed to build a second human bakery and a gas chamber. In the original crematorium alone, they turned 11,000 human bodies into ash.

Looking at those vestiges of mass murder takes you back in time, so much so that you can envision them when they were in use: The fires burned right in there. Someone carried a body here and stuffed it in there. Then they shut this door and took the ashes out of that one.

Standing outside the gas chamber: Guards led inmates — up to 150 at a time — over here, told them they’d be showering in there, and had them strip their clothes (which others would wear). Once the prisoners walked inside, someone locked those doors, and someone over here dumped canisters of Zyklon-B poison gas into that vent, there. The gas pills dropped in, and the guard closed the vent.

A few minutes later, men went in and removed the bodies. The victims, who were poisoned and suffocating, tried desperately to reach the unreachable ceiling vents before they died. This created a corpse pyramid. The gas also caused them, records state, to defecate and vomit all over the floor.

All bodies and their outputs were promptly removed and burned or washed away, readying the room for the next lucky group.

These things happened. Here.

I stepped inside the gas chamber.

It was an empty room. Brick walls, tile floor, drywall ceiling. Vents and drains here and there. It looked like an old high school gym’s group shower. It was supposed to look like a group shower.

To my right: the poison gas vent. I walked over to it, grasped the bars, and peered out where I had previously looked in.

Then — right there in the gas chamber — I sat down.

The floor was cold. A few people stood in the room, but I pictured those who’d been there before. Then those people left, and others walked in. Others left, and others came in.

And I felt … peace.

It was one of the strangest and more moving sensations of my life. In Berlin, and Munich, and certainly all that day in Dachau, my thoughts and emotions had dwelled on the past — on anger, on sorrow, on death, on man’s capacity for evil. On resistance, survival, pride and prevention.

But in the middle of that gas chamber: Peace.

The whole day had been filled with pain. In that gas chamber, though, the pain subsided. I was able to see it for what it had been — of course — but I could see it, also, for what it had become: an empty room. I saw people entering and exiting, from all parts of the world, assembled there to bear witness and to understand. It showed me how even the greatest evil can be transformed into a tremendous good.

The crematoria, the gas chamber, the bunker, the barracks, the roll call grounds … they have all lost their former power. Their power now is cautionary; they have been reduced to artifacts, reminders of the past that teach us in the present. That is all they are.

Eventually, our Brazilian friend, Natalia, walked into the room. She noticed me sitting down and walked over. She patted me on the shoulder and said, in her Portugese accent, “Everything is fine, Sam.”

I smiled and rose to my feet.

After we left the gas chamber, our tour group stood around the “Statue of the Unknown Prisoner,” which bears the inscription (in German): “To Honor the Dead, To Warn the Living.”

Curt gave me the opportunity to address our international group of more than 20 people. Other than myself, there were only two other Jews.

“I just want to thank all of you for coming,” I said. “Growing up Jewish, you learn a ton about Holocaust history, but you don’t really know how it’s taught all across America, let alone in the rest of the world. And you worry that people won’t learn about it. To see people here from so many different places, to know that people care about it and that it’s not just something that affects Jews, it really means a lot to me. So thank you.”

Later, I asked Curt how he’d describe the general German attitude, or feeling, toward the Holocaust.

“Shame,” he said. “Utter shame.”

According to him, Germans now regard anti-Semitism with the utmost seriousness. He related the tale of a neo-Nazi who posed for a picture, two thumbs up, in front of Dachau. Curt said the man “got in a whole mess of trouble.”

Finally, he told me that Germans no longer sing any kind of patriotic songs — and hardly any others, for that matter — in public. “Because under Hitler,” he said, “they used to sing songs all the time.”

At first, we weren’t sure it was the Holocaust memorial. I’ve been to Yad Vashem in Israel and the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and there in Berlin all we saw were large, stone blocks spread over a plot of white-powdered earth. Like giant tombstones — 2,711 of them.

“This has got to be it,” Travis said.

Our only indication — a plaque nearby — described the history of the “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” The area was first utilized in 1688 and had had many different tenants, but this caught my attention: “It came to be used as the office-villa of the Reich Propaganda Minister, Dr. Joseph Goebbels.” One of Hitler’s right-hand men. The plaque also said the site formed part of the Berlin Wall-era “death strip,” where guards shot people trying to cross the border.

Now, it serves as a memorial — to honor the dead, to warn the living.

“Liebe,” she said. “Love.”

“Why did you write this?” I asked her.

She twisted a lock of hair in her finger. “Because this is an important place,” she said. “We have to remember what happened here. And I think that love is a good message.”

For some reason, I blurted it out: “I’m Jewish.”

She gave me a look of sincere compassion. “This must have a lot of meaning for you.”

She’ll never know how much.

— Post-writing note:

My grandmother sat across from me at lunch, holding a printed copy of the story above. “You know the memorial in Berlin?” she asked me.

“Yeah …”

“Your cousin was the architect.”

“Come again?”

“Yeah – Peter Eisenman. He’s your cousin.”

I sat there, stunned. This site that had made such an impact on me had been designed by one of my relatives, and I’d had no idea until afterward.

Coincidence? Who knows.

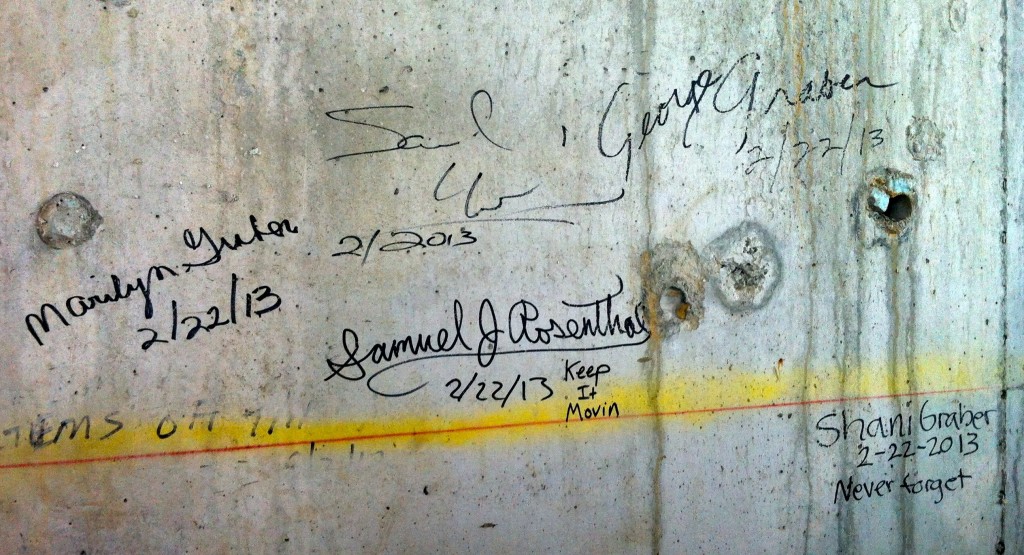

Email Sam Rosenthal at samrose24@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter: @BackwardsWalker

by

by  by

by

It’s not like I’ve stopped adventuring, either. I was able to re-visit Madrid, and Chapel Hill. I journeyed to Ocean City, MD, Monticello, NY, and Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. I’ve ridden the Staten Island Ferry, attended the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, toured the United States Constitution Center, rocked karaoke at a Spanish wedding, and etched my name in Sharpie on the interior walls of the new One World Trade Center. (Don’t worry, I had police permission.)

It’s not like I’ve stopped adventuring, either. I was able to re-visit Madrid, and Chapel Hill. I journeyed to Ocean City, MD, Monticello, NY, and Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. I’ve ridden the Staten Island Ferry, attended the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, toured the United States Constitution Center, rocked karaoke at a Spanish wedding, and etched my name in Sharpie on the interior walls of the new One World Trade Center. (Don’t worry, I had police permission.)