In the southern Spanish region of Andalucia, on the Costa del Sol, lies Nerja (see map and zoom out). It’s a travel agent’s dream — a tourist haven that has retained its native charm without becoming a giant souvenir shop. Stunning views of the Mediterranean Sea abound, especially at the Balcón de Europa (the Balcony of Europe). The food, the weather and the town’s relaxed feel all help make Nerja a wonderful place, but it enchanted me for a different reason: its caves.

When my friends David and Vanesa told me we could see caves in Nerja (NER-hah), it piqued my interest because, being that I’m no seasoned spelunker, I’d never seen the inside of a cave before. Yet what I imagined paled in comparison to reality.

Outside Las Cuevas de Nerja is a statue dedicated to the five men who discovered them in 1959. The grounds are perfectly maintained in a jungle-meets-seaport-meets-suburbia kind of way. They are beautiful, as are the young women who offer you commemorative cave photos, which are similar to the ones you purchase after riding a theme park roller coaster. (Naturally, they suckered me into buying one for 8 euro.)

Entering the cave, we saw a plaque, once again honoring the cave’s discoverers. It seemed kind of silly to me — these guys discovered one little cave, and they’re heroes?

One little cave, my aspirin.

The main vestibule thrilled me, although it did conform more or less to my expectations. The crystal formations exceeded anything I’d ever seen in a jewelry store, and the collection of human artifacts was fascinating: fragments of knives and axes, bracelets and necklaces, entire bowls and hand millstones, pieces of clothing. Illustrations and accompanying texts described human cave settlements, which began appearing in about 25000 B.C. and continued until the Bronze Age (approximately 3000 B.C.). Perhaps someone should notify the Spanish IRS; that’s over 20,000 years of unpaid taxes.

Seeing all that, I wondered to myself: “Self, how many times do you come across human history that’s 26,000 years old?”

Then they told me that many of the crystals took two million years to form. The cave itself began forming approximately five million years ago.

“Oh my God,” I thought. “That’s, like … older than my parents.”

One vestibule sign said there were other halls in the cave. I exited the vestibule, walked down a flight of stairs, and woah — my breath was ripped from my chest by the scene before me.

As you know, a writer’s job is to take people, places, things and experiences and bring them to life in the readers’ minds. The general rule is that nothing should be termed ‘indescribable’ because, if you’re a good writer, you should be able to find words to describe everything.

Though there’s something to that, some things are way more difficult to describe than others. So let me begin by saying this: No words, to me, will fully depict or do justice to the incredible beauty of that place.

Still, to give you an idea …

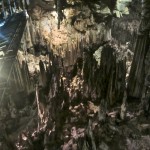

Stretching out in front of my eyes was a great hall that measured about a football field wide, half a football field high (if football fields climbed vertically), and God-knows-how-many football fields long; I couldn’t see where it terminated off in the distance. The sight froze me in place … and as I stood there in awe, five or six other people did the same exact thing, stopped dead in their tracks by the cave’s ethereal power.

Eventually, I made my way down the stairs and saw the area where the annual Festival Internacional de Música y Danza (International Festival of Music and Dance) is held. (Not making this stuff up.) To my left was a crystal formation covered in some green, algal or fungal overgrowth. Out came the camera, and within moments I was lying on my back, trying to capture with photos what I’m currently trying to capture with words.

Leaving the ballroom, I entered what’s known as the Chamber of the Cataclysm. They could call it the Cathedral Chamber as well — St. Peter’s would probably fit inside. In that chamber, my breath came short, my steps shorter as the place’s aura gripped my mind. Humans are terrific architects — don’t get me wrong — but nothing we build holds a candle to Nature’s designs. This was one of Mother Earth’s most breathtaking basement units, 5 million years in the making.

And some of it’s still under construction. Water, that unbelievably slow-working but effective power tool, continues to sculpt new crystals in the caves. The moist air feels like a bathroom after a shower, except colder and with a slight scent of mildew.

The variety of rock formations astonished me. They have stalactites and stalagmites, naturally, but also formations known as soda straws, pineapples, nails, pearls and so on. The immature observer can also find many thallus-shaped rocks — not that anyone in our expedition would be so uncouth as to do such a thing.

At one point, I read a sign advertising the chamber’s central column, which apparently is the largest of its kind in the world. (Guinness Record and everything.) So I looked for the thing — “Is that it? Doesn’t look like the Guinness Record holder …”

Then I turned around. “Oh. That might just could be what they’re talking about.”

In front of me was a pillar of solid rock, spanning from cavern floor to ceiling, 32 meters (about 105 feet) tall, and about 20 sequoias in diameter. I had hit the Rock Bottom-less. The Empire Slate Building. The U.S.S. Ulysses S. Granite. It looked like something strong enough to hold up the world … which, in a way, is exactly what it does.

The place gave me goosebumps, and it was quite obvious from the looks and expressions of the caves’ other visitors that they shared my sediments — sentiments, that is. Nature is one of the few things that can deliver such an incredible sensation of awe in us, and for me it serves as a reminder of what an incredible world this is and what a special thing it is to be alive and to have the ability to appreciate it.

So often we forget, or overlook, what mysteries the world holds. Five guys stumbled on a hole in the ground one day, and they ended up discovering a palace more intricate than Versailles, a cavern that’s literally older than dirt. Think about that — five million years! I’ve been here 25, and if I make it to 80 I’ll consider that pretty good. But five million? That’s beyond comprehension. And to walk among those crystals and touch them and feel connected to so much that came before …

It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been, with a power you can only understand if you visit it yourself. It is a power that I’ve tried to depict as best I can, but I don’t feel that I’ve come remotely close to the truth.

For some things, words and pictures … well, let’s just say that they don’t delve nearly deep enough.